HOME / PROCLAMATION! MAGAZINE / 2016 / SUMMER / OPEN THEISM

S U M M E R • 2 0 1 6

VOLUME 17, ISSUE 2

Martin Carey grew up as a “nomadic” Adventist in many places. He works as a school psychologist in San Bernardino, California. Married to Sharon, he has two sons, Matthew, 14, and Nick, 27. Astronomy, research, and too many pets keep him in joyful disarray. You may contact him at martincarey@sbcglobal.net.

Editor’s note: One of the preconceived ideas we as Adventists held—an idea shared with many Christians as well—is that of ultimate human self-determination. Even God, we were taught, values our free will above His own authority. We at Life Assurance Ministries (LAM), however, believe there is mystery we cannot explain in the biblical statements of God’s absolute foreknowledge and of its commands to us to believe. Both are true. Nevertheless, God is the ultimate authority in the universe, not our free will. Martin Carey’s article examines the clear dangers of the “openness of God” theology that permeates Adventism and is creeping into evangelicalism. We pray this article will draw readers to worship the God revealed in Scripture who sees, knows, and saves us.

How do we know for sure that God will triumph over Satan in the end? We are horrified by the evil in the world, and sometimes we wonder guiltily if God is losing His control. As Christians, we look forward to the world ending as described in Revelation 20, with God flinging the dark forces into the Lake of Fire and gathering a multitude of people who have remained safely and willingly loyal to Him.

On the other hand, His enemy is also gathering followers, and in much greater numbers. When God’s enemies appear to oppose Him successfully, how can we be sure that He will triumph?

Seeing this spiritual battle over human loyalties raises some hard questions. As Seventh-day Adventists, in fact, we often asked those questions in Sabbath School discussions that went something like this:

“How can we have free will if God is sovereign?” someone would ask. “Why is there so much suffering? Why won’t God do more to stop Satan?” Someone else would give our automatic answer, “Because we have free will, and God doesn’t want robots programmed to love Him.” We liked that answer—even though something seemed to be missing.

As Adventists, free will was one of our core values, and yet we all knew that sooner or later, life would deliver an ugly surprise that would make us plead with God, “Why have you forgotten me?” (Ps. 42:9). We loved our freedom, but when tragedy hit, we wanted God to take strong action—we wanted Him to take control.

We may think free will is at the heart of our identity, yet when tragedy strikes, we need a truly sovereign God who has the power to work all things for our good. The therapy books tell us to look inside ourselves for strength, but self-affirmations are hollow and temporary. Deep inside, we know that “When other helpers fail and comforts flee,” as the songwriter said, we need assurance that is firmly anchored to rock-bottom reality.

One Foundation

Our great controversy worldview made us uncomfortable with a strong sovereign God. Because we believed that God’s purposes are often frustrated by Satan, we could not fully embrace God’s central revelation: “I am God!” We were blinded to the implications in Isaiah chapters 40 to 48 where God declares Himself to be the only divine power and puts all the other gods on trial, exposing them as frauds.

“Tell us what is to come hereafter, that we may know that you are gods; do good, or do harm, that we may be dismayed and terrified. Behold, you are nothing!” (Is. 41:23, 24).

In His word the one true God directs us to Himself—the Rock—and proclaims why He is worthy of our confidence:

“I am God, and there is none like me, declaring the end from the beginning and from ancient times things not yet done, saying, ‘My counsel shall stand, and I will accomplish all my purpose’” (Is. 46:9,10).

As Adventists we were disconnected from 2000 years of Christian heritage, of confidence in God’s never-failing control of history, and of His declaration of everything that will happen in the future. We believed we had superior understanding, and we disdained the simple trust of Christians who submitted to God’s will. Instead, we demanded that God must respect our choices.

Christians, however, have always known they can trust God’s rule, not only because He is loving, but also because He knows exactly how He will fulfill His purposes. In fact, while both Arminians and Calvinists have differed on how God’s sovereignty and our free wills interact, they have always agreed on God’s perfect, exhaustive foreknowledge. For example, Jacobus Arminius wrote, “[God] has known from eternity which persons should believe . . . and which should persevere through subsequent grace.”1 John Calvin expressed it this way: “[God] foresees future events only by reason of the fact that he decreed that they take place.”2

A new idea takes shape

In recent years, however, a fascination with free will and a God who limits His power to protect our autonomy has developed within the Christian church. This movement denies God’s perfect foreknowledge and portrays Him as a limited being like us. In fact, one of the leading spokespeople for this belief is a Christian pastor and author, Gregory Boyd, who says that God does not know all that the future will bring. Another Christian promoter of this idea, Clark Pinnock, says, “The future does not yet exist and therefore cannot be infallibly anticipated, even by God”.3 This view, called open theism, says God leaves the future open to our free choices, and our decisions don’t exist until we create them from nothing. Thus, they are unknowable beforehand, even by God. Boyd says:

In the Christian view God knows all of reality—everything there is to know. But to assume He knows ahead of time how every person is going to freely act assumes that each person’s free activity is already there to know—even before he freely does it! But it’s not. If we have been given freedom, we create the reality of our decisions by making them. And until we make them, they don’t exist.4

For open theists, the future is an ongoing cooperative project between God and His creatures—a construct that probably sounds much like the Adventist worldview. Within this framework, all our hopes for the future are tentative, depending on unforeseen decisions we and other humans will make. If history is largely shaped by human choices within this paradigm, then God’s foreknowledge is limited to gathering facts and making the best predictions He can. These “facts”, say the open theists, don’t include our future free choices; therefore, God’s predictions can be wrong. However, says Clark Pinnock, God is very wise and knows all the “contingencies,” all the events that might happen:

Nothing can happen that God is not prepared for and in his wisdom cannot handle. His anticipation of future contingencies is perfect.5

Within open theism, therefore, God is never surprised by any event, even if it is one chance out of trillions, because He, like a supercomputer, has anticipated all possibilities before they happen. Presumably, open theism’s God can effectively prepare for a vast number of different outcomes without specifically having foreknowledge of what will actually occur.

If we believe that God is ignorant about much of the future, however, His “perfect anticipation” is of small comfort. He limits Himself to living inside of time as we do, so moment by moment, He awaits all our unforeseeable decisions that force Him to keep changing His plans. When He miscalculates, He regrets His decisions and learns from those experiences. In fact, Boyd compares this version of divine “foreknowledge” to the risk calculations used by insurance agents, although God’s database of risks is much greater than theirs.6 If God were to write insurance policies under this scheme, He could only mitigate disasters by paying out settlements after the disasters happen. This “open God” is unable to prevent most evils, arriving late to clean up after Satan and to fix the damages as best He can.

If this “openness” scenario is God’s “providence,” though, we must trust not only in God’s power but also in His good luck. If our theology reduces God, so that He is not the Sovereign who turns the king’s heart wherever He wills (Prov. 21:1) and determines the times and boundaries of every nation on earth (Acts 17:26), our faith in Him is also reduced. As Bruce Ware has said,

While claiming to offer meaningfulness to Christian living, open theism strips the believer of the one thing needed most for a meaningful and vibrant life of faith: absolute confidence in God’s character, wisdom, word, promise, and the sure fulfillment of his will.7

This view of an “open” God who limits Himself to protect our free will is not new to Adventism. In fact, for 172 years, Ellen White’s great controversy paradigm has kept Adventists struggling to finish “the work” because Adventism’s Jesus depends on their work to make His return possible.

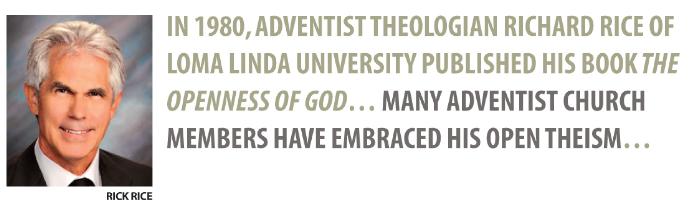

Now, over the last 20 years, the openness movement has entered into mainstream Christianity and keeps gaining respectability. Seventh-day Adventist theologian Richard Rice from Loma Linda University found common ground with open theology, becoming a major figure early in the movement. Rice and evangelical theologians such as Clark Pinnock, John Sanders, and Gregory Boyd—professors at established colleges who were not influenced by Adventist theology—have succeeded in promoting open theism into the mainstream in both the Adventist church and much of evangelicalism. Today openness theology has a growing presence on campuses, in churches, and in Christian bookstores.

Open Theism in history

There have been several movements throughout church history that have embraced variations of “openness”. Faustus Socinus (Fausto Sozzini), 1539 to 1604, came from a prominent Italian family, and although he befriended the reformers Melancthon and Calvin, he had major differences with them. Socinus believed that faith must be agreeable to reason, leading him to see the incarnation—God becoming man—as an irrational doctrine. He denied that Jesus was God and insisted that His atonement on the cross was not a payment for sin to satisfy God’s justice. Thus, to Socinus, the cross was only a dramatic display of God’s forgiving love. Socinus’ God does not have wrath to be appeased; He forgives because His will is free; His just nature does not determine what He “must” do. Therefore, in addressing sin, this God does whatever suits Him at the moment. He doesn’t need a blood sacrifice for our sins in order to forgive them. Moreover, because of our free will, we don’t need a substitute; we only need Jesus as our example of making moral choices, showing us the way to salvation.8

Socinus denied that God can have perfect foreknowledge of the free choices of his creatures. God foreknows “necessary” future events, but has only partial knowledge of free choices.9 In Socinus’ view, if God knows infallibly that something will happen, then that event must come to pass, and no one is free to change it. For Socinus, any theology that tries to combine God’s perfect foreknowledge with our free will is an illusion.10

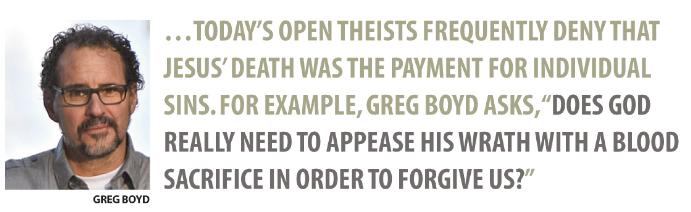

Modern open theism shares some of the main ideas of 16th century Socinianism. Although today’s open theists do not deny Christ’s divinity, they frequently deny that Jesus’ death was the payment for individual sins. For example, Greg Boyd asks, “Does God really need to appease his wrath with a blood sacrifice in order to forgive us?” He then gives ten reasons why he opposes the penal substitution view of the atonement.11

For open theists, sin is not about guilt before the holiness and justice of God. Sin is “alienation,” says open theologian John Sanders; it is a broken relationship with God.12 From this perspective, Christ came to demonstrate God’s love and to show the way to salvation. Openness theology says we restore our relationships with Him by making good choices and living out Christ’s example.

According to open theologians, God’s loving nature greatly limits His power to govern. Although Scripture makes it clear that God’s ultimate purpose is to glorify Himself (Is. 43:25; Ez. 36:22; Jn. 12:27-28; Eph. 1:5; Phil. 2:9-11), open theists claim that God’s ultimate purpose is to experience free, authentic relationships with His creatures. Therefore, they say, God created men and angels who could share power with Him and, if they chose, freely oppose and frustrate His plans. In fact, Gregory Boyd insists that perfect human freedom is necessary for us genuinely to love God. This perfect freedom we supposedly have, therefore, means that our relationships with God include mutual risk, pain, and joy, just as we experience in relationship with each other.13 Clark Pinnock agrees:

God, in grace, grants humans significant freedom to cooperate with or work against God’s will for their lives, and he enters into dynamic, give-and-take relationships with us. The Christian life involves a genuine interaction between God and human beings.14

Radical Free Will

Open theism’s central assumption that controls all its beliefs is not a confidence in God; rather, it is a belief in human libertarian free will. This libertarian, or radical, free will is supposedly marked by free choices which are purely self-created, uncaused by anything in creation or by God. According to open theists, a strictly free choice is not even caused by our desires, since desires are shaped by our experiences, genetic makeup, and environment.15 Even though our personalities and experiences influence our choices, they will explain, libertarian free choices are not determined by any of those influences. Until the moment we choose, therefore, our wills are indifferent, equally able to choose among opposite alternatives. Open theists call this radical freedom of the will the “liberty of indifference.”

This confusing premise leads to some questions. If our free choices are not caused by any part of “us”, can our choices really be considered ours? Do we really choose at all, or is our freedom of choice more like rolling the dice? If our free choices are only mental accidents, how can we be held morally responsible for them?16

Lacking biblical support for this idea, Boyd appeals to quantum mechanics to bolster his theory:

Quantum mechanics has demonstrated that this uncertainty is not due to our limited measuring devices; it is actually rooted in the nature of things. This means that even on a quantum level the future is partly open and partly settled.17

Quantum physics, in fact, is well known for strange goings-on. Physicists cannot predict with precision what any one particle will do. In fact, “Nothing physical determines quantum events,” declares the current scientific consensus on quantum mechanics.18 In open theism’s universe, however, the freedom of uncertainty has been given not only to subatomic particles but also to men and angels as well. If the tiniest particles are unpredictable, they reason, then human choices are equally accidental.

Boyd takes a wild metaphysical leap by claiming that God, like us, is unable to determine or predict the behavior of quantum events. If physicists are unable to predict or control all the movements of particles, the open theist believes that God is likewise limited, confounded by the very things He created.

Openness theology imagines that free will needs a free universe in order to flourish. In other words, free choices are made possible by God’s limited power and the wild randomness of nature. This belief, however, leads to another question: if nature is fundamentally chaotic, if even God must submit to its randomness, why should we trust Him with the future? If He is a being much like us, constrained by His own creation, then He, like we do, waits and hopes for an uncertain future. How do we trust a God who is as surprised as we are by future events?

Disturbingly, the wild, radical freedom of open theism also demands that our choices be completely detached from everything we feel or experience as “real.” This belief, however, leads to an unsolvable dilemma: if our choices have nothing to do with our desires, how do we respond to God with our whole heart, soul, strength, and mind? After all, Jesus said that this mandate is the first and greatest commandment:

“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself” (Lk. 10:27).

Luke’s passage echoes the psalmist, and both define loving God as desiring God, consciously giving Him control of all our desires and attachments:

“Whom have I in heaven but you? And there is nothing on earth that I desire besides you. My flesh and my heart may fail, but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever” (Ps. 73:25).

The Freedom Worth Having

The previous texts show us that loving God means willfully giving our entire selves—our hearts, souls, strength, and minds—over to His control. This submission even of our wills, however, is antithetical to openness theology and its claims of radical freedom. So, if Scripture describes loving God as submitting to him, how does Scripture describe our freedom?

Jesus said this, “If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” (Jn. 8:31, 32).

The Jews who heard Him didn’t believe Him; they thought they had freedom as sons of Abraham (vs. 33) and had no need of Jesus. He answered,

“Truly, truly, I say to you, everyone who practices sin is a slave to sin. The slave does not remain in the house forever; the son remains forever. So if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed” (vs. 34, 35).

Here Jesus alludes to Hagar and Ishmael who were slaves in the house of Abraham. Any natural child of Abraham who sins is a type of slave like Ishmael, and not a son. Slaves like Hagar and Ishmael have no permanent place in the home and ultimately are cast out. Only the Son—in this case the descendant of Isaac, the child of promise, could be the sole and permanent heir. Jesus’ hearers knew that Isaac, not Ishmael, was the true heir of Abraham. What they didn’t want to acknowledge was that the true Son of promise, Jesus, redeems the slaves of sin, both Jew and Gentile, and sets them free. Outside of Him, they—and we—could only be slaves.

Jesus defined freedom to his stubborn listeners as the condition of being set free from sin by Him and then of abiding in His word and thus knowing truth. In other words, knowing Jesus, and knowing the truth in His word, sets people free. In contrast with the open theists, Jesus and His word define freedom not as a universal, natural endowment independent of one’s will and of God, but as the condition of being forgiven and released from sin, then being able to know the truth in His word.

Man’s original freedom was degraded by sin, so none are naturally free; all are under sin (Rom. 3:9-18). The natural man wants his independence; he is hostile against God (Rom. 8:7, 8), a slave of sin (Jn. 8:34), and incapable of acting outside of his nature. We are morally accountable for our sin, even though we are slaves to it and cannot make holy choices. In other words, we are only free to act on our corrupted desires—while paradoxically we are held responsible for our sin which we are helpless to avoid.

The Bible, however, defines true freedom as liberty from sin, for all of us are slaves to sin unless we die to the old self by sharing in His death (Rom. 6:6-8). Liberty is obtained by adoption into the household of Christ (Gal. 4:5-7). He makes us alive in Him (Eph. 2:5-7) and gives us new hearts that make us “slaves to righteousness” (Rom. 6:15-23).

The Gods at War

Open theism presents a different picture of God than Scripture gives us. Openness says He took grave risks in creating angels and man with radical freedom—a freedom which carried a heavy price for God. In spite of His splendid creation, Adam and Eve sinned. Their fall came as a surprise to God, for in the perfections of Eden, sin was “implausible.”19 Their sin ushered in evil and suffering, but His loving nature and moral purity prevented Him from interfering with the free choices of men and angels.

Concurrently, open theology’s Satan is a ruthless, independent agent of evil whose free choices God does not foreknow. In fact, he can surprise God with his powers which resemble those of the gods of mythology.20 Gregory Boyd illustrates this view of Satan by describing the warfare worldview of the Shuar tribe in Ecuador, a primitive people who attribute all disaster and death to unseen evil spirits. The Bible, he says, supports the Shuar’s fears of constant supernatural warfare and explains all of life’s good and bad events as the effects of war between powerful spirits.21 The good powers are not in control of the universe, Boyd says, for “God chose to create a quasi-democratic cosmos in which dualism could result.”22

In a universe shaped by warfare between a limited God and an unrestrained Satan, God’s promise to cause “all things to work together for good to those who love God” (Rom 8:28) has no meaning. Open theist John Sanders discusses the meaning of incurable cancer striking a two-year old child:

It is a pointless evil. The holocaust is pointless evil. The rape and dismemberment of a young girl is pointless evil. The accident that caused the death of my brother was a tragedy. God does not have a specific purpose in mind for these occurrences.23

Open theists claim that evil angels continually force God to deviate from His original intentions for His creation. How, then, is God’s will accomplished? Pinnock answers that God is “endlessly resourceful and competent in working toward his ultimate goals,” even though He “does not control everything that happens.”24

Ironically, open theism’s elevation of evil’s freedom and power ultimately contradicts its central doctrine of free will. For example, if evil spirits can interfere with God’s hearing or answering one’s prayers25 or can freely plan and execute disaster for one’s children,26 or if evil can enter a person’s mind to victimize another,27 all without God’s foreknowledge or plan, one cannot claim to have real freedom. Ultimately, what begins as a theology of freedom becomes a paradigm of fear and bondage.

When we take power away from God, we transfer it to the forces of nature or to other beings. Do we feel freer believing Satan is in control of evil than we do having our Creator and Savior in charge?28

The New Testament describes the God-given role of Satan and puts him in his rightful place. He is certainly a murderer and a liar (Jn. 8:44) and a deceiver who rules those who do not belong to God (Eph. 2:1-3; 1 Jn. 5:19). He also is allowed, under God’s strict supervision, to bring trouble to God’s people. Paul tells of a “messenger of Satan” that was given to him, a thorn in the flesh to harass him and keep him from pride. When he asked God three times to remove it, God answered, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my strength is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:7-9). Satan’s harassment was God’s tool for Paul’s good.

The overwhelming message of God’s word is that the infinite, sovereign God controls Satan and by Himself rules history. In fact, while the Israelites were being invaded by Babylon’s armies, God told them,

“Do not fear what they fear, nor be in dread. But the LORD of hosts, him you shall honor as holy. Let him be your fear, and let him be your dread. And he will become a sanctuary” (Is. 8:12-14).

Open theists, on the contrary, say that God cannot plan for evil or suffering in any form, for such foreknowledge would make Him guilty of causing the event.29 They claim it is pointless to look for some divine plan in tragedy, as Christians have always done because of God’s promise in Romans 8:28: “And we know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose.” Greg Boyd interprets the text to mean, “Whatever happens God will work with us to bring a redemptive purpose out of the event.”30

The text does not say, however, that God is working with us to bring good purposes out of events, after they happen. Verse 29 contains His purpose, “For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son.” The words are precise; “predestination” states a pre-existing purpose of God to make us like His Son. In all things, even terrible things, God is working His purposes for us, because He planned for us to be changed through those events.

In open theism, radical free will is the wild card that threatens the destiny of the universe. In Scripture, God’s will is carried out in the heavens and on earth (Dan. 4:35; Eph. 1:11), but in openism, God’s will is often frustrated by His godlike adversary. Bruce Ware sums up the consequence of openness well:

“Cosmic warfare theology gives us a perilous, demon-haunted future—the price we must pay for the radical freedom of open theism. God has been locked in fierce combat against Satan and his angels, with God doing all he can, often unsuccessfully, to oppose evil.”31

The Great Controversy

In 1980, Adventist theologian Richard Rice of Loma Linda University published his book The Openness of God,32 and as a college student at La Sierra, I found his world view very enticing. Many Adventist church members have embraced his open theism, especially around Loma Linda, California, where professors Jack Provonsha and A. Graham Maxwell also taught for decades.33 They denied Christ’s penal substitutionary atonement and portrayed a universe engulfed in cosmic warfare, much like the views of Boyd, Sanders, and Rice.

Open theism’s cosmic warfare scenario, in fact, has a familiar ring to Seventh-day Adventists acquainted with Ellen White’s great controversy theology. The great controversy theme (GCT) claims to be a “theory of everything”, as Herbert Douglass put it, and “introduces us to the mind of God.”34 Satan has been allowed to tempt and destroy because, according to White, God has to defend His character against Satan’s accusations. Satan was successful in putting God on the defensive before the court of the universe. Being on the defensive, God’s actions to save man are primarily motivated to save His reputation against Satan’s accusations. That controversy spread from heaven and enveloped our earth after man’s fall, as Herbert Douglass explained:

Open theism’s cosmic warfare scenario, in fact, has a familiar ring to Seventh-day Adventists acquainted with Ellen White’s great controversy theology. The great controversy theme (GCT) claims to be a “theory of everything”, as Herbert Douglass put it, and “introduces us to the mind of God.”34 Satan has been allowed to tempt and destroy because, according to White, God has to defend His character against Satan’s accusations. Satan was successful in putting God on the defensive before the court of the universe. Being on the defensive, God’s actions to save man are primarily motivated to save His reputation against Satan’s accusations. That controversy spread from heaven and enveloped our earth after man’s fall, as Herbert Douglass explained:

“Satan has charged (and influenced men and women to believe) that God is unfair, unforgiving, and arbitrary. God’s defense has been both passive and active passive; in that He has allowed time to proceed so that Satan’s principles could be seen for all their suicidal destructiveness.”35

In the great controversy God is forced to allow Satan and his evil hordes to operate with minimal restraint. God’s plans and actions are controlled by circumstances, driven along by threats and demands that He didn’t plan or want. According to Ellen White, God is defending himself in a cosmic lawsuit and needs to win his case before untold billions of innocent, inquiring aliens. Satan was allowed access to “tempt and annoy” the unfallen beings of countless worlds, putting doubt in their minds.36 Why does Satan have the freedom to continue his destructive rampage?—for the security of the whole universe! Says White,

“It was God’s purpose to place things on an eternal basis of security, and in the councils of heaven it was decided that time must be given for Satan to develop the principles which were the foundation of his system of government…Time was given for the working of Satan’s principles, that they might be seen by the heavenly universe.”37

In fact, White depicts a heavenly scene where God gathered a “council” to discuss the disasters of sin and death initiated by Satan. The committee decided to use caution, realizing Satan’s rampage needs to continue until the entire universe is agreed on Satan’s utter badness. God’s salvation timeline, therefore, depends on many factors, including His political standing in the cosmic popularity polls, and on human obedience to His laws. In the great controversy, God is portrayed more like the harried prime minister of a troubled democracy, than the supreme monarch “who works all things according to the counsel of his will” (Eph. 1:11).

Boyd’s cosmic warfare has a different emphasis than White’s, claiming that, because God gave sovereign power over to His creatures, the universe is now under the rule of more than one “god.”38 Boyd acknowledges that God is infinite in wisdom and goodness, but contends that his radical free will experiment permitted his arch enemy to grow extremely powerful. Unlike Boyd, White generally accepts God’s perfect foreknowledge,39 but she weakens God’s sovereign control with a cosmic lawsuit where God must defend His character against a powerful accuser.

In spite of some differences, however, we can see that open theism and great controversy theology have elements in common:

1. Radical free will is the core value that governs God’s relationships with angels and men, so that, like God, their choices have ultimate power to shape the future.

2. Satan’s freedom and power are godlike. Satan has the power to frustrate God’s plans, bringing vast destruction, death, and pointless evil to God’s creatures. Evil must be allowed to rule, not because God uses evil to glorify Himself, but as White said, “time must be given for the working of Satan’s principles.”

3. The gospel of Christ was “Plan B.” Satan’s rebellion disrupted God’s original plan for His creation, so that Jesus’ dying and rising for sinners was not God’s original purpose, but a countermeasure to Satan’s work.

Ultimately, if openism and the great controversy reveal the “mind of God,” we see a limited being who can fail, one who is embattled and outmaneuvered by the growing power of Satan.

Integrity of the Gospel

The gospel of Jesus Christ is a great test to measure the integrity of our theologies, so let us apply that test to open theism. Although open theists generally accept that Jesus somehow died for our sins so that we are saved by God’s grace, that faith is damaged by openism’s central assumptions. If God cannot know the future of our free choices, the New Testament gospel of salvation is changed. Let’s look at two ways that open theism profoundly distorts the gospel.

First, under openism none of God’s promises are certain. Rather, they are conditional, depending upon the uncertain, future choices of men and angels. Contrary to this belief, however, God’s covenant with Abraham has detailed promises that must happen as promised by God; otherwise, they are null and void. Consider, for example, this prophecy where God pledged His covenant to Abraham’s offspring:

“Know for certain that your offspring will be sojourners in a land that is not theirs and will be servants there, and they will be afflicted for four hundred years. But I will bring judgment on the nation that they serve, and afterward they shall come out with great possessions” (Gen. 15:13, 14).

There was no legal fine print or escape clause in that covenant. Many free human choices were involved in making the prophecies come true, such as the sins of Joseph’s brothers recorded in Genesis 50:15-20. Nevertheless, these sins ultimately led to Israel suffering the horrors of slavery for 400 years under Pharaoh, just as God had said—and then they were delivered. All these details occurred just as God declared they would—and yet, God was not the cause of those sins.

The mysterious interplay of human choice and God’s sovereign promises and foreknowledge appear to be contradictory. Humans struggle to explain how these interactions “work”. In truth, however, both human choices and God’s sovereign foreknowledge are true. The Bible is clear that both are true, and we are expected to accept both as true without forcing a resolution that will satisfy our logic.

Another argument against God’s foreknowledge uses the “I regret” statements of God. These texts are supposed to show that God changes His mind about a past decision, after He sees it was a mistake. Consider 1Samuel 15:11:

“I regret that I have made Saul king, for he has turned back from following me and has not performed my commandments.”

Later in the same chapter, however, we learn what He meant by “regret”:

“The Lord has torn the kingdom of Israel from you this day and has given it to a neighbor of yours, who is better than you. And also the Glory of Israel will not lie or have regret, for he is not a man, that he should have regret.”

God’s regrets are not feelings of remorse for mistakes. Certainly God has complex feelings about His interactions with the world,40 but He is not like fallible men who lie or change their minds. If He spoke, He will fulfill His word (Num. 23:11-15). God can, however, feel sorrow about something He knew was painful but necessary to do, such as appointing Saul as king as part of the divine plan that would ultimately usher in Saul’s neighbor David, a better man, as king. In fact, David’s family line was already foreordained to bring Messiah into the world. Saul’s tribe was Benjamin, but the Messiah must come from Judah, according to the prophecies. As Jesus said, the word of God “cannot be broken” (Jn. 10:35).

Second, within open theism the gospel becomes impersonal. If God cannot know future human choices, He cannot know the identities of any of us prior to our births. Furthermore, an “open” God has not known who would come to Him and believe, or who would be saved or lost. It also means that none of Jesus’ work was done for us personally. Yet Isaiah 53 tells what the suffering Servant came to do for us, people that didn’t know Him:

Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; yet we esteemed him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his wounds we are healed (vs. 4, 5).

He came to bear our griefs and our sins in Himself, so that we might be healed and have peace with God. However, under openism, Jesus did not know that any of us would exist, so when He suffered, He did not bear any of our personal sorrows or sins. Those griefs and sorrows were not real pains that any of us actually have felt, but generic sorrows for anonymous people of the future. Under openism, Jesus could not have borne our personal sins 2000 years ago. Instead, His death was an impersonal death for unknown people who might or might not believe.41

But His death was personal. Peter tells us, “He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness” (1 Pet. 2:24). This is a personal exchange between Jesus and us. While we were His enemies our sins were laid on Him, so He could give His life and righteousness to those He foreknew. “We love because He first loved us” (1 Jn. 4:19). Those who love God were foreknown by Him and predestined to become like His Son (Rom. 8:28, 29). He loved us first, chose us and adopted us, that we should be blameless before Him (Eph. 1:4,5). In God’s mind, He has already justified and glorified us (Rom. 8:30), as an accomplished fact of history. We are comforted knowing His foreknowledge is so deeply personal.

Concurrently, we are commanded to believe. God knows how to lead us to the Son and how to impact us with the truth of the gospel. He has no need to force our wills to bend to Him; His ways are gentle, but His purposes for His children never fail. Jesus said to the Jews that the work of God is to believe in the One whom He sent (Jn. 6:29). He also said that He who believes will not come into judgment, but he who does not believe is condemned already (Jn. 3:18).

There is a mystery here which we cannot explain. Instead of attempting to create a formula to explain these apparently opposing facts, our proper response is to believe that both are true. God’s sovereign knowledge of our choices does not remove our responsibility to choose rightly. When we hear God’s command to believe, our proper response is to obey, knowing that God had full knowledge of our moment of decision before we ever were born.

Before the Foundation of the World

As the final chapter of history closes, it will appear that evil is winning. There is a terrible beast, an overwhelming political power with great signs and wonders to deceive. The dragon gives the beast authority to rule over every tribe and people on the earth so that they worship the beast. By all appearances, the forces of darkness will have finally prevailed, dominating the world and stopping God’s kingdom. Almost everyone on earth will worship the evil power—with one small exception:

“…everyone whose name has not been written before the foundation of the world in the book of life of the Lamb who was slain” (Rev. 13:8).

At the world’s end time there are two groups of people; a very large group who worship the beast, and a little group who are not deceived, whose names are written down in “The Book of Life of the Lamb”. Later, in Revelation 17:8, the world—all those whose names are not in the Lamb’s book of life from the foundation of the world—marvels at the beast. The decisive difference between the two groups is whether or not their names are recorded in the book. What is it about that book that prevents people from following the most evil power in history?

Before Adam and Eve sinned, before the creation of the world, before Satan rebelled, the book of the slain Lamb was written. In the eternal counsels of God, the Trinity knew that sin would come and the plan for sin was already set in place. Sin didn’t require an emergency “heavenly counsel” to decide, after the fact, what to do with Satan and sinners. No, as God said through Isaiah, He declared His counsel from the beginning, and it still stands (Is. 46:9). God first decreed that the Lamb was to be slain for sinners, long before there was sin. It was as good as done, for He had already recorded the names of those to be saved by His blood.

But why so much suffering? We long for the bliss of the new earth where we will be free from the consequences of our fallen state, but now we find answers whenever the gospel is preached. Peter presents the eternal viewpoint on the Day of Pentecost, when he preached that the very Jesus who was “delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men” (Acts 2:23). Before Jesus came to earth as a man, in God’s mind He was already crucified for sinners. Jesus’ execution by evil men was, by God’s plan, “predestined to take place” (Acts 4:28), for He was always the slain Lamb, “foreknown before the foundation of the world” (1 Peter 1:19).

Jesus, the Lamb to be slain, created the universe and everything in it for His own glory and purposes (Is. 42:8; 43:7; 48:9-11; Col. 1:16). The earth was made to be the theater of His perfections, where the Son would exhibit the greatest wonder of all, showing grace to sinners.42 Sin and suffering were no surprise to God, for they serve His eternal purposes. Jesus came to bear our griefs and carry our sorrows, redeeming them and giving us eternal glory with Him.

“I Lay It Down”

We know that God’s “very good” creation was put in place for us to see His glory. It may seem strange that He would create a beautiful cosmos for the purpose of entering into it to suffer and die, yet these things all happened according to His eternal counsel: “Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” (Lk. 24:26). Our Creator does not gamble with His own glory, betting on reckless creatures with uncertain futures. Neither does He need luck, for He upholds all things by His word. In fact, He sat down with his disciples and told them what He was about to do, of His own free will:

“For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life that I may take it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have authority to lay it down, and I have authority to take it up again. This charge I have received from my Father” (Jn. 10:18).

Jesus made a free, sovereign choice in perfect submission to His Father—a choice predetermined from all eternity. Two thousand years of prophecy foretold His death, and the night before His trial, Jesus gave His disciples the sure sign of true sovereignty. When Judas was about to betray Him, He told the twelve, “I am telling you this now, before it takes place, that when it does take place you may believe that I am” (Jn. 13:19). The pronoun “He” is not in the Greek; Jesus identified Himself as the “I AM”, the One in Isaiah 46 who declares the end from the beginning, whose counsel will stand. He said He would be betrayed and slain (Mt. 17:22) to give His life as a ransom for many. As God He decreed, and as the Son of Man, He fulfilled. There was no “chance” that Jesus could have failed, for failure to fulfill His promise would make God a liar. What He speaks, He accomplishes.

Today, many Christians are afraid that if God is fully sovereign, He is also untouched by our pain. They fear He will crush their freedom, so they flee to weak, unthreatening versions of Him. A weak God, however, cannot keep His promises or protect us from ourselves or from the kingdom of Satan.

If we would know the true Father—the One who is powerful enough to keep us safe from all evil, we must know the Lord Jesus of Scripture. If we reject this sovereign, powerful God and His Son who shed His blood to pay for our sins, we will prefer our darkness (Jn. 5:36-40).

In Christ, all the power and glory of God dwells, and He is the one who faithfully carries all of our sorrows. Today, He commands us to surrender our wills and choose Him above all imitators.

We do not serve an “open God” who gambles our futures in a battle with Satan. Rather, we serve a victorious King, and in the endless years of eternity, we will never cease praising the mighty, terrible Lion who is the Lamb who was wounded for us.

“Worthy are you to take the scroll and to open its seals, for you were slain, and by your blood you ransomed people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation” (Rev. 5:9). †

Endnotes

- Carl Bangs, Arminius, Quoted in Taste and See: Savoring the Supremacy of God in All of Life, John Piper, Crown Publishing Group, 2009, p. 212.

- Ibid.

- Clark Pinnock and Delwin Brown, Theological Crossfire: An Evangelical/Liberal Dialogue, Wipf and Stock, Publishers, 1998, p. 130.

- Gregory Boyd, Letters From a Skeptic: A Son Wrestles With His Father’s Questions About Christianity, David C. Cook, 2010, p. 38.

- Clark Pinnock, Ibid.

- Martyn McGeown, Closing the Door On Open Theism, Covenant Reformed Protestant Church, http://www.cprf.co.uk/articles/opentheism.htm#.VtUk-M72ZCE

- Bruce A. Ware, God’s Lesser Glory, Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2000, p. 21.

- Sam Storms, Socinianism, http://www.samstorms.com/all-articles/post/socinianism/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Gregory Boyd, Ten Problems With the Penal Substituion View of the Atonement, http://reknew.org/2015/12/10-problems-with-the-penal-substitution-view-of-the-atonement/

- John Sanders, The God Who Risks: A Theology of Divine Providence, Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, Illinois, p. 105.

- Gregory Boyd, The Risk of Love and the Source of Evil, http://reknew.org/2014/08/the-risk-of-love-the-source-of-evil/

- Clark Pinnock, Richard Rice, John Sanders, John Hasker, David Basinger, The Openness of God, A Biblical Challenge to the Traditional Understanding of God, InterVarsity Press, 2010, p. 7.

- John Frame, “Open Theism and Divine Foreknowledge”, 2001, http://frame-poythress.org/open-theism-and-divine-foreknowledge/

- John Frame, Ibid.

- Gregory Boyd, God of the Possible, Baker Books, 2000, p. 109-110.

- John Beckman, Modern Physics and the Open View of God, 2001. http://www.reclaimingthemind.org/papers/ets/2001/Beckman/Beckman.pdf

- John Sanders, The God Who Risks: A Theology of Providence, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1998, p. 46.

- Boyd, God at War, InterVarsity Press, 1997, p. 12.

- Gregory Boyd, Ibid, p. 19.

- Ibid, p. 176.

- John Sanders, The God Who Risks: A Theology of Providence (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1998), p. 262.

- Clark Pinnock, et al, The Openness of God, p. 7.

- Gregory Boyd, Ibid, p. 10-11.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, pp. 199-200.

- Chad Brand, Ibid, p. 68.

- Gregory Boyd, Ibid, p. 142.

- Gregory Boyd, God of the Possible, p. 155.

- Bruce Ware, Ibid, p. 28.

- Richard Rice, The Openness of God, Review and Herald Pub. Assoc., 1980.

- A. Graham Maxwell, Atonement: Quotes by Graham Maxwell, Pineknoll online.

- Herbert Douglass, “The Great Controversy Theme: What it Means to Adventists”, Ministry Magazine, December, 2000, https://www.ministrymagazine.org/archive/2000/12/the-great-controversy-theme

- Herbert Douglass, Ibid.

- Ellen White, The Great Controversy Between Christ and Satan, Pacific Press Publishing Association, 1911, p. 659.

- Ellen White, The Desire of Ages, Pacific Press Publishing Association, 1898, p. 759.

- Gregory Boyd, God at War, p. 119.

- See for example, Ellen White, The Desire of Ages, p. 22, God foresaw the fall of Satan and man.

- John Piper, Glory of God at Stake in God’s Foreknowledge of Human Choices

- Bruce Ware, The Gospel of Christ, Ch. 9, Out of Bounds, Edited by John Piper, Justin Taylor, Paul Kjoss Helseth, Crossway Books, 2003, p. 333.

- Alfred Barnes, Notes on the Bible, Colossians 1:16, “For Him,” Biblehub.com, http://biblehub.com/commentaries/colossians/1-16.htm

Copyright 2016 Life Assurance Ministries, Inc., Camp Verde, Arizona, USA. All rights reserved. Revised August 23, 2016. Contact email: proclamation@gmail.com